2 Why We Code

Before writing your first line of code, it’s crucial to clearly understand what you’re trying to achieve—specifically, the purpose of your research. This helps you focus on developing an innovative solution that creates real value by improving existing approaches or addressing unmet needs. Furthermore, this clarity will enable you to communicate your research effectively to ensure your audience understands the benefits of your work.

Why We Develop Software

While programming can be enjoyable in its own right, most people—and especially companies—aren’t willing to invest significant time or resources unless there’s a clear return. So why do we write code in the first place?

Please note that there is a difference between code and a software product:

- Code is simply text written in a programming language (like Python).

- A software product is code that actually runs—either locally (on your laptop or phone) or remotely (as a web service in the cloud)—and produces an output that users interact with.

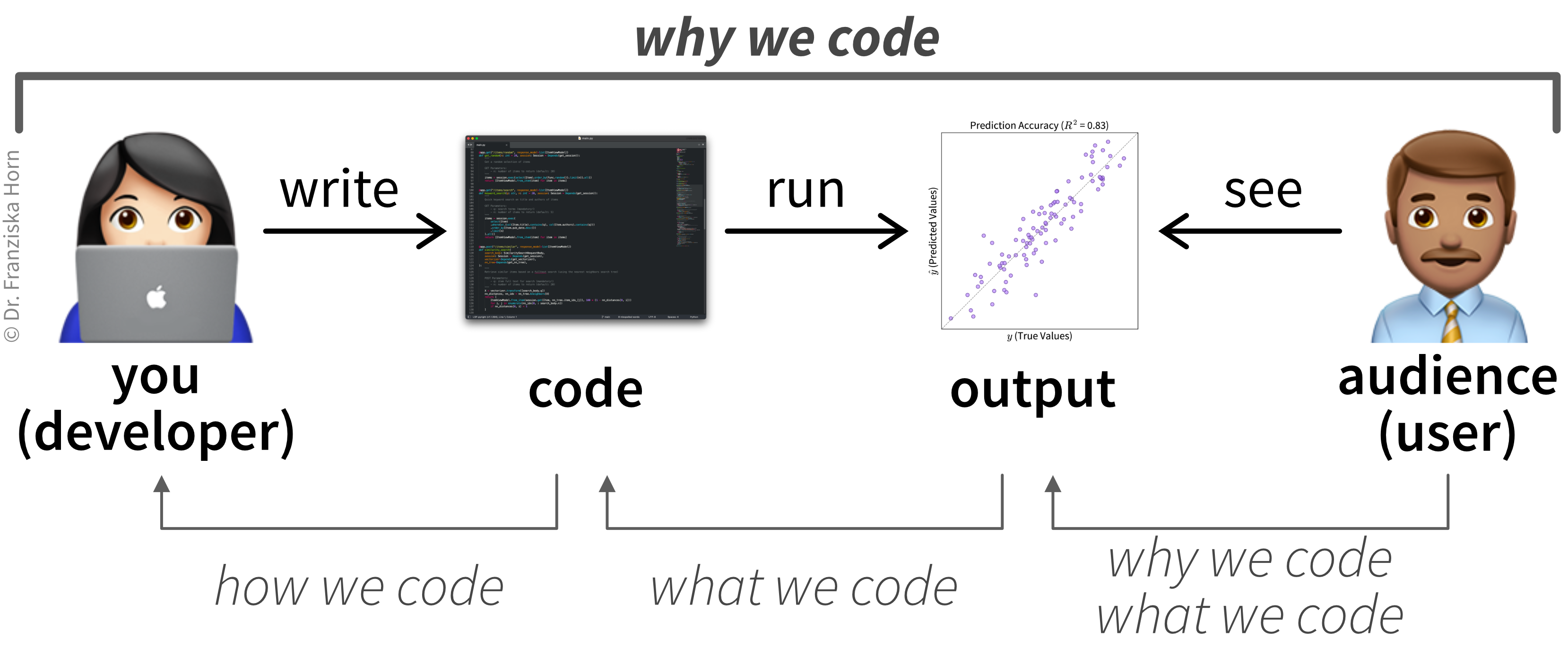

Sometimes that interaction with the program is the end goal (e.g., when playing a video game). Other times, the software is just a means to an end—like a website you use to order clothes online or the script you run to generate your research results (Figure 2.1).

When it comes to serious software development, the motivation usually boils down to profit and/or recognition.

Companies are usually looking to make a profit, which can be accomplished in one of two ways:

Increase revenue: The company builds a software product or feature that customers are willing to pay for—for example, a web application offered as software-as-a-service (SaaS) with a monthly subscription.

Reduce costs: Alternatively, companies might build internal tools that automate tedious or repetitive tasks. By saving employee time, these tools reduce operational costs and indirectly increase profit.

As an individual—especially in research—your primary goal is probably to get some recognition in your field. For instance:

- You might write code to generate results that get your paper published in a respected journal and cited by others.

- Or you might create an open-source library that becomes popular (and receives a lot of stars on GitHub).

With a bit of luck, that recognition may eventually lead to profit, such as landing a well-paid job based on a successful side project.

Innovative Solutions

Whatever your motivation, success—whether financial or reputational—only comes if your software meets a real need. In other words, it must create value for your users.

We’ll explore how to do this in more detail in the next chapter. For now, it’s enough to say that this usually requires an innovative idea: something that solves a problem better than existing alternatives—at least for a specific group of users.

This principle isn’t limited to software. Imagine you’re a company developing a new woodworking tool. You might identify an underserved market segment—say, young women—and, through surveys, discover that current tools are too heavy and noisy. These insights inspire you to design a quieter, lighter tool.

At this stage, you still don’t know whether you can actually build it—it might turn out that such a tool isn’t technically feasible. But you’ve at least identified a meaningful gap in the existing market and a problem worth solving—enough to justify investing time and resources to try and develop an innovative solution.

In research, the goal is similar: to advance the state of the art. That might mean filling a gap in knowledge, or developing a new method, material, or process with improved properties. In your area of expertise, you’re probably already aware of something that could be improved—where existing approaches fall short and where your idea might offer a better solution.

Depending on the type of research, implementing your idea might require a lot of programming—or very little. You might need to program a simulation model, or just generate a few plots for a paper or presentation.

The next section gives an overview of common research goals and the types of data analysis needed to achieve them. We’ll then look at how to quantify your intended outcomes—identifying the key metrics that your idea should improve. Finally, we’ll explore how to visually communicate your research purpose, since visuals are often the most effective way to explain complex ideas.

Types of Research Questions

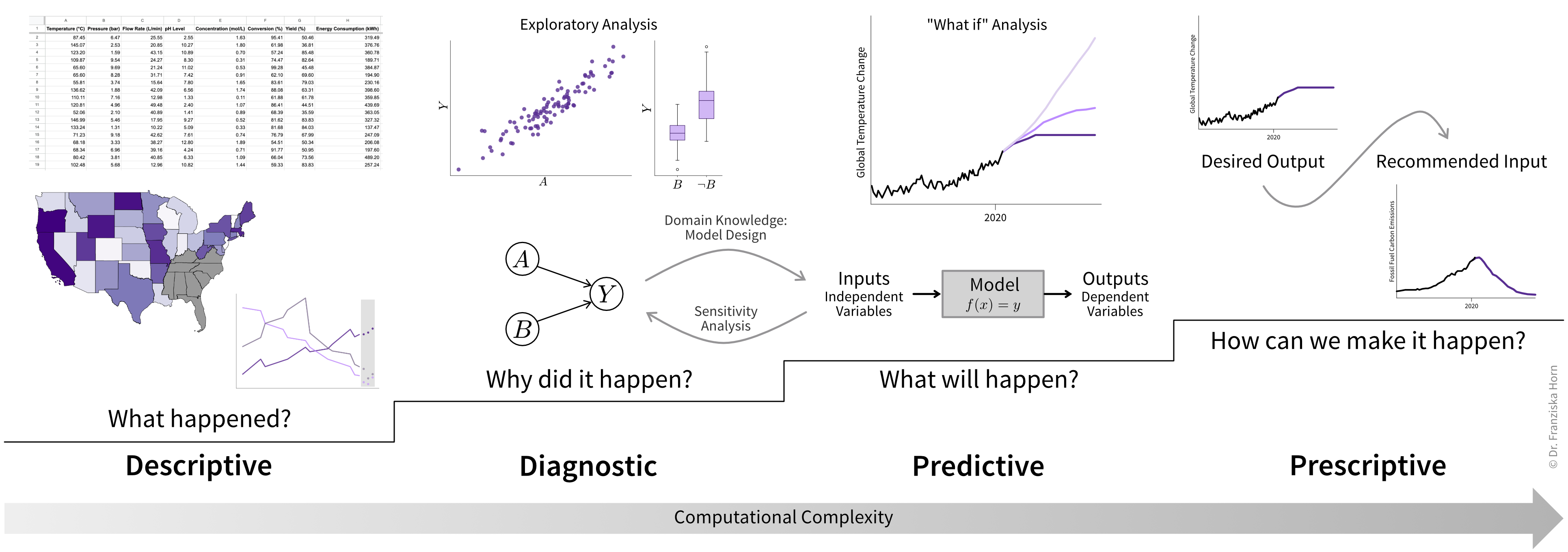

Most research questions can be categorized into four broad groups, each associated with a specific type of analytics approach (Figure 2.2).

Descriptive Analytics

This approach focuses on observing and describing phenomena to establish baseline measurements or track changes over time.

Examples include:

- Identifying animal and plant species in unexplored regions of the deep ocean.

- Measuring the physical properties of a newly discovered material.

- Surveying the political views of the next generation of teenagers.

Methodology:

- Collect a large amount of data (e.g., samples or observations).

- Calculate summary statistics like averages, ranges, or standard deviations, typically using standard software tools.

Diagnostic Analytics

Here, the goal is to understand relationships between variables and uncover causal chains to explain why phenomena occur.

Examples include:

- Investigating how CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels drive global warming.

- Evaluating whether a new drug reduces symptoms and under what conditions it works best.

- Exploring how economic and social factors influence shifts toward right-wing political parties.

Methodology:

- Perform exploratory data analysis, such as looking for correlations between variables.

- Conduct statistical tests to support or refute hypotheses (e.g., comparing treatment and placebo groups).

- Design of experiments to control for external factors (e.g., randomized clinical trials).

- Build predictive models to simulate relationships. If these models match real-world observations, it suggests their assumptions correctly represent causal effects.

Predictive Analytics

This method involves building models to describe and predict relationships between independent variables (inputs) and dependent variables (outputs). These models often rely on insights from diagnostic analytics, such as which variables to include in the model and how they might interact (e.g., linear or nonlinear dependence). Despite its name, this approach is not just about predicting the future, but used to estimate unknown values in general (e.g., variables that are difficult or expensive to measure). It also includes any kind of simulation model to describe a process virtually (i.e., to conduct in silico experiments).

Examples include:

- Weather forecasting models.

- Digital twin of a wind turbine to simulate how much energy is generated under different conditions.

- Predicting protein folding based on amino acid sequences.

Methodology:

The key difference lies in how much domain knowledge informs the model:

White-box (mechanistic) models: Based entirely on known principles, such as physical laws or experimental findings. These models are often manually designed, with parameters fitted to match observed data.

Black-box (data-driven) models: Derived primarily from observational data. Researchers usually test different model types (e.g., neural networks or Gaussian processes) and choose the one with the highest prediction accuracy.

Gray-box (hybrid) models: These combine mechanistic and data-driven approaches. For example, the output of a mechanistic model may serve as an input to a data-driven model, or the data-driven model may predict residuals (i.e., prediction errors) from the mechanistic model, where both outputs combined yield the final prediction.

Resources to learn more about data-driven modelsIf you want to learn more about how to create data-driven models and the machine learning (ML) algorithms behind them, these two free online books are highly recommended:

- [2] Supervised Machine Learning for Science by Christoph Molnar & Timo Freiesleben; a fantastic introduction focused on applying black-box models in scientific research.

- [3] A Practitioner’s Guide to Machine Learning by me; a broader overview of ML methods for a variety of use cases.

After developing an accurate (!) model, researchers can analyze its behavior (e.g., through a sensitivity analysis, which examines how outputs change with varying inputs) to gain further insights about the modeled system itself (to feed back into diagnostic analytics).

Prescriptive Analytics

This approach focuses on decision-making and optimization, often using predictive models.

Examples include:

- Screening thousands of drug candidates to find those most likely to bind with a target protein.

- Optimizing reactor conditions to maximize yield while minimizing energy consumption.

Methodology:

Decision support: Use models for “what-if” analyses to predict outcomes of different scenarios. For example, models can estimate the effects of limiting global warming to 2°C versus exceeding that threshold, thereby informing policy decisions.

Decision automation: Use models in optimization loops to systematically test input conditions, evaluate outcomes (e.g., resulting predicted material quality), and identify the best conditions automatically.

Model accuracy is crucialThese recommendations are only as good as the underlying models. Models must accurately capture causal relationships and often need to extrapolate beyond the data used to build them (e.g., for disaster simulations). Data-driven models are typically better at interpolation (predicting within known data ranges), so results should ideally be validated through additional experiments, such as testing the recommended new materials in the lab.

Together, these four types of analytics form a powerful toolkit for tackling real-world challenges: descriptive analytics provides a foundation for understanding, diagnostic analytics uncovers the causes behind observed phenomena, predictive analytics models future scenarios based on this understanding, and prescriptive analytics turns these insights into actionable solutions. Each step builds on the previous one, creating a systematic approach to answering complex questions and making informed decisions.

Evaluation Metrics

To demonstrate the impact of your work and compare your solution against existing approaches, it’s crucial to define what success looks like quantitatively. Consider these common evaluation metrics to measure the outcome of your research and generate compelling results:

- Number of samples: This refers to the amount of data you’ve collected, such as whether you surveyed 100 or 10,000 people. Larger sample sizes can provide more robust and reliable results. But you also need to make sure your sample is representative of the population as a whole, i.e., to avoid sampling bias.

- Reliability of measurements: This evaluates the consistency of your data. For example, how much variation occurs if you repeat the same measurement, e.g., run a simulation with different random seeds. This is important as others need to be able to reproduce your results.

- Statistical significance: The outcome of a statistical hypothesis test, such as a p-value that indicates whether the difference in symptom reduction between the treatment and placebo groups is significant.

- Model accuracy: For predictive models, this includes:

- Standard metrics like \(R^2\) to measure how closely the model’s predictions align with observational data.

- Cross-validation scores to assess performance on new data.

- Uncertainty estimates to understand how confident the model is in its predictions.

- Algorithm performance: This includes metrics like memory usage and the time required to fit a model or make predictions, and how these values change as the dataset size increases. Efficient algorithms are crucial when scaling to large datasets or handling complex simulations.

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): Any other practical measures that matter in your field. For example:

- For a chemical process: yield, purity, energy efficiency.

- For a new material: strength, durability, cost.

- For an optimization task: convergence time, solution quality.

Your evaluation typically involves multiple metrics. For example, in prescriptive analytics, you need to demonstrate both the accuracy of your model and that the recommendations generated with it led to a genuinely optimized process or product. Before starting your research, review similar work in your field to understand which metrics are standard in your community.

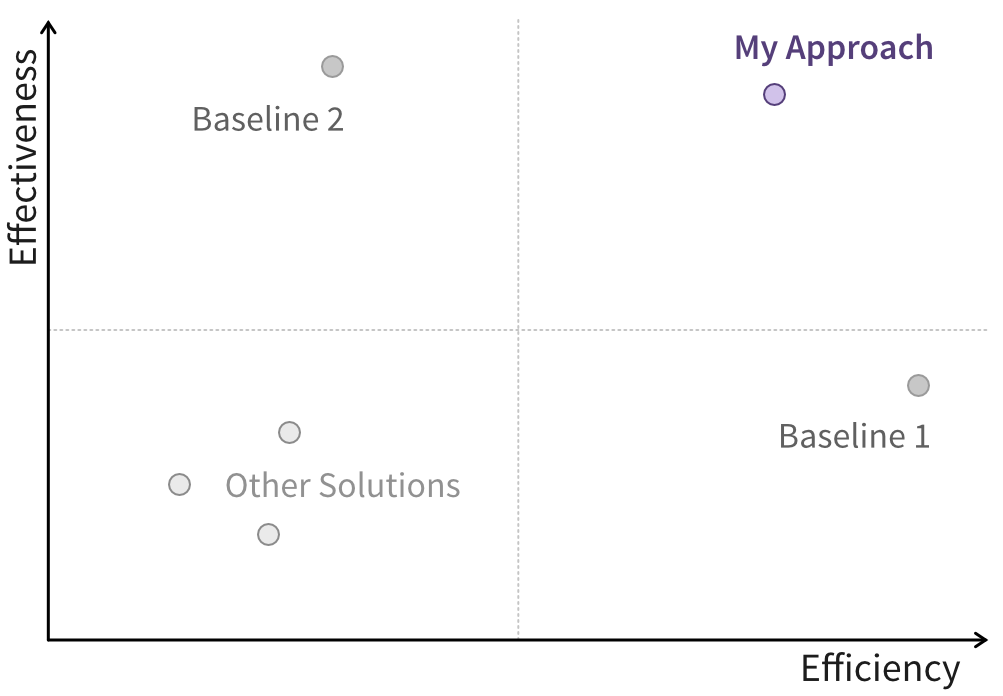

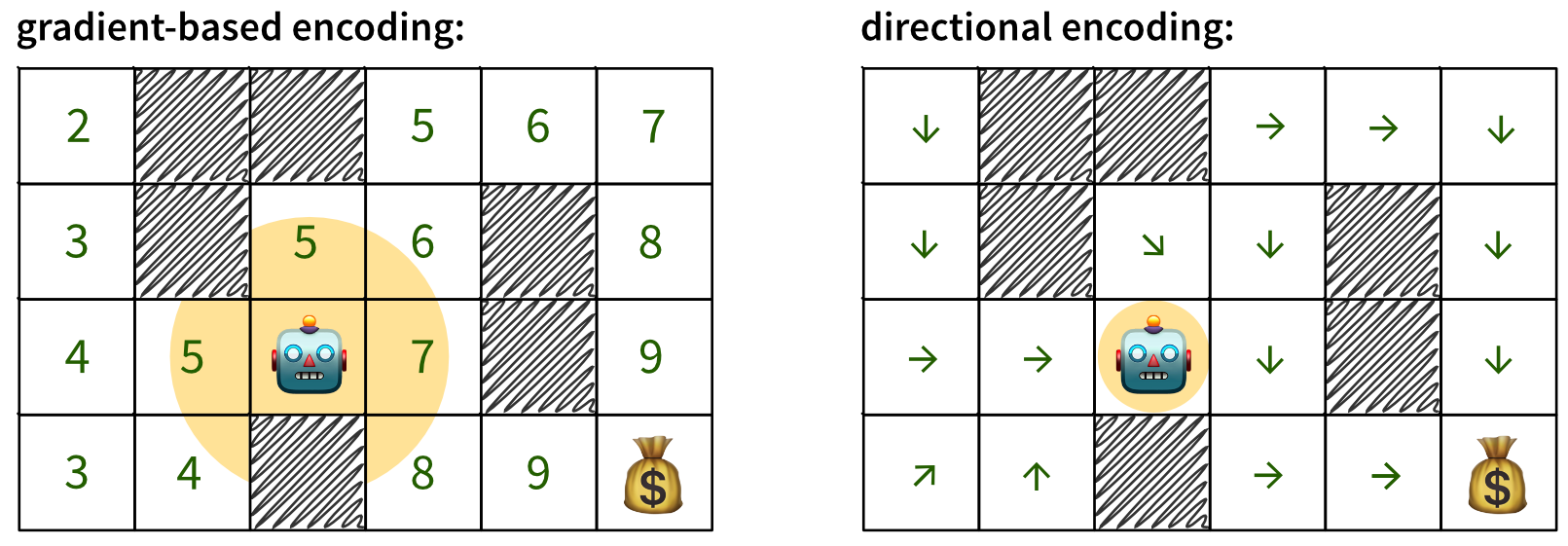

Ideally, you should already have an idea of how existing solutions perform on your chosen metrics (e.g., based on findings from other publications) to establish the baseline your solution should outperform. You’ll likely need to replicate at least some of these baseline results (e.g., by reimplementing existing models) to ensure your comparisons are not influenced by external factors. But understanding where the “competition” stands can also help you identify secondary metrics where your solution could excel. For example, even if there’s little room to improve model accuracy, existing solutions might be too slow to handle large datasets efficiently (Figure 2.3).1

These results are central to your research (and publications), and much of your code will be devoted to generating them, along with the models and simulations behind them. Clearly defining the key metrics needed to demonstrate your research’s impact will help you focus your programming efforts effectively.

Draw Your Research Goal

Whether you’re collaborating with colleagues, presenting at a conference, or writing a paper—clearly communicating the problem you’re solving and your proposed solution is essential.

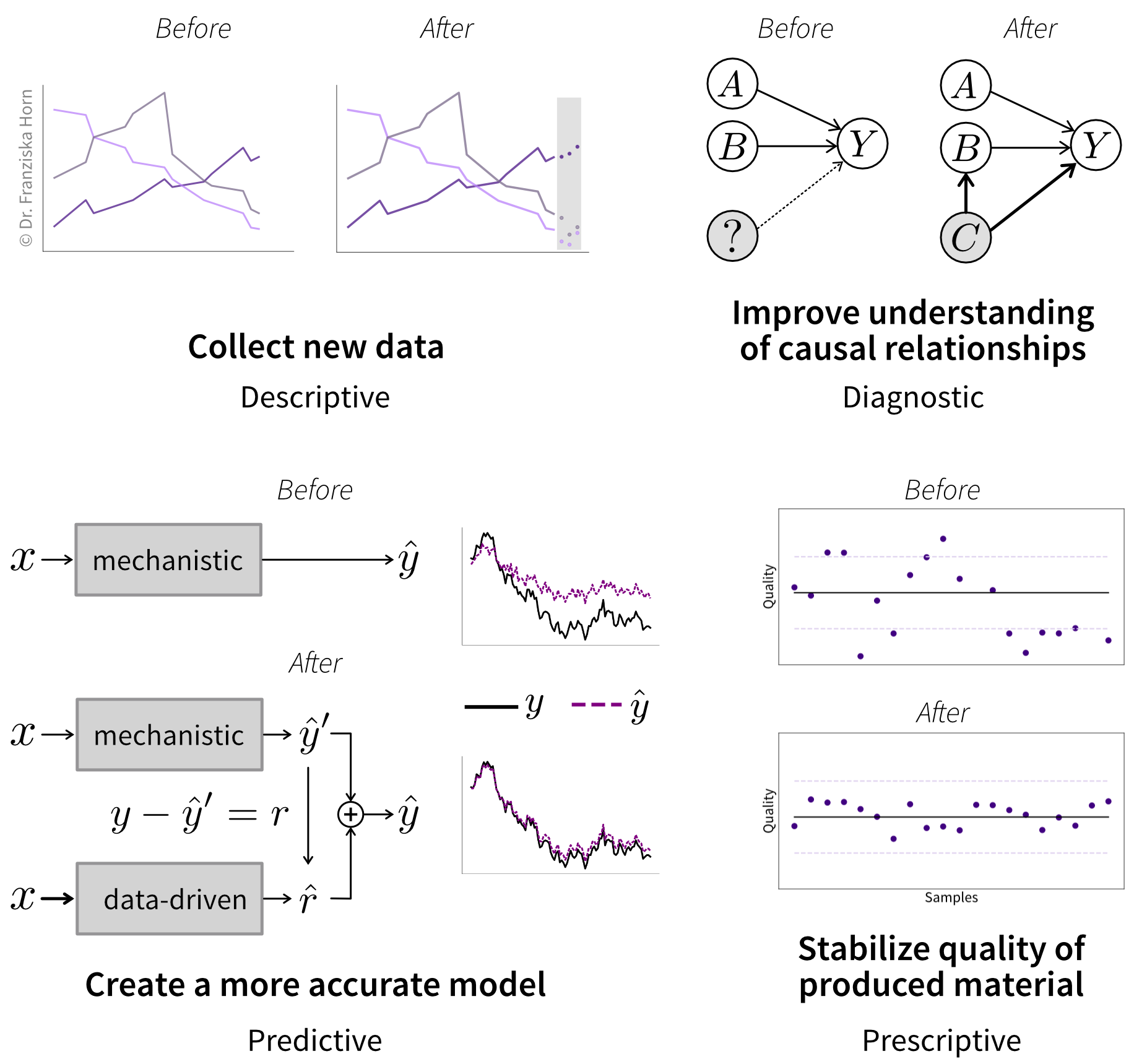

Visual representations are particularly powerful for conveying complex ideas. One effective approach is creating “before and after” visuals that contrast the current state of the field with your proposed improvements (Figure 2.4).

The “before” scenario might show a lack of data, an incomplete understanding of a phenomenon, poor model performance, or an inefficient process or material. The “after” scenario highlights how your research addresses these issues and improves on the current state, such as refining a predictive model or enhancing the properties of a new material.

At this point, your “after” scenario might be based on a hypothesis or an educated guess about what your results will look like—and that’s totally fine! The purpose of visualizing your goal is to guide your development process. Later, you can update the picture with actual results if you decide to include it in a journal publication, for example.

Of course, not all research goals are tied directly to analytics. Sometimes the main improvement is more qualitative, for example, focusing on design or functionality (Figure 2.5). Even in these cases, however, you’ll often need to demonstrate that your new approach meets or exceeds existing solutions in terms of other key performance indicators (KPIs), such as energy efficiency, speed, or quality parameters like strength or durability.

Give it a try—does the sketch help you explain your research to your family?

At this point, you should have a clear understanding of:

- The problem you’re trying to solve.

- Existing solutions to this problem, i.e., the baseline you’re competing against.

- Which metrics should be used to quantify your improvement on the current state.

For example, currently, a lot of research aims to replace traditional mechanistic models with data-driven machine learning models, as these enable significantly faster simulations. A notable example is the AlphaFold model, which predicts protein folding from amino acid sequences—a breakthrough so impactful it was recognized with a Nobel Prize [1]!↩︎